Reviews

CD Review

Audio Society of Atlanta

By Phil Muse

February 2012

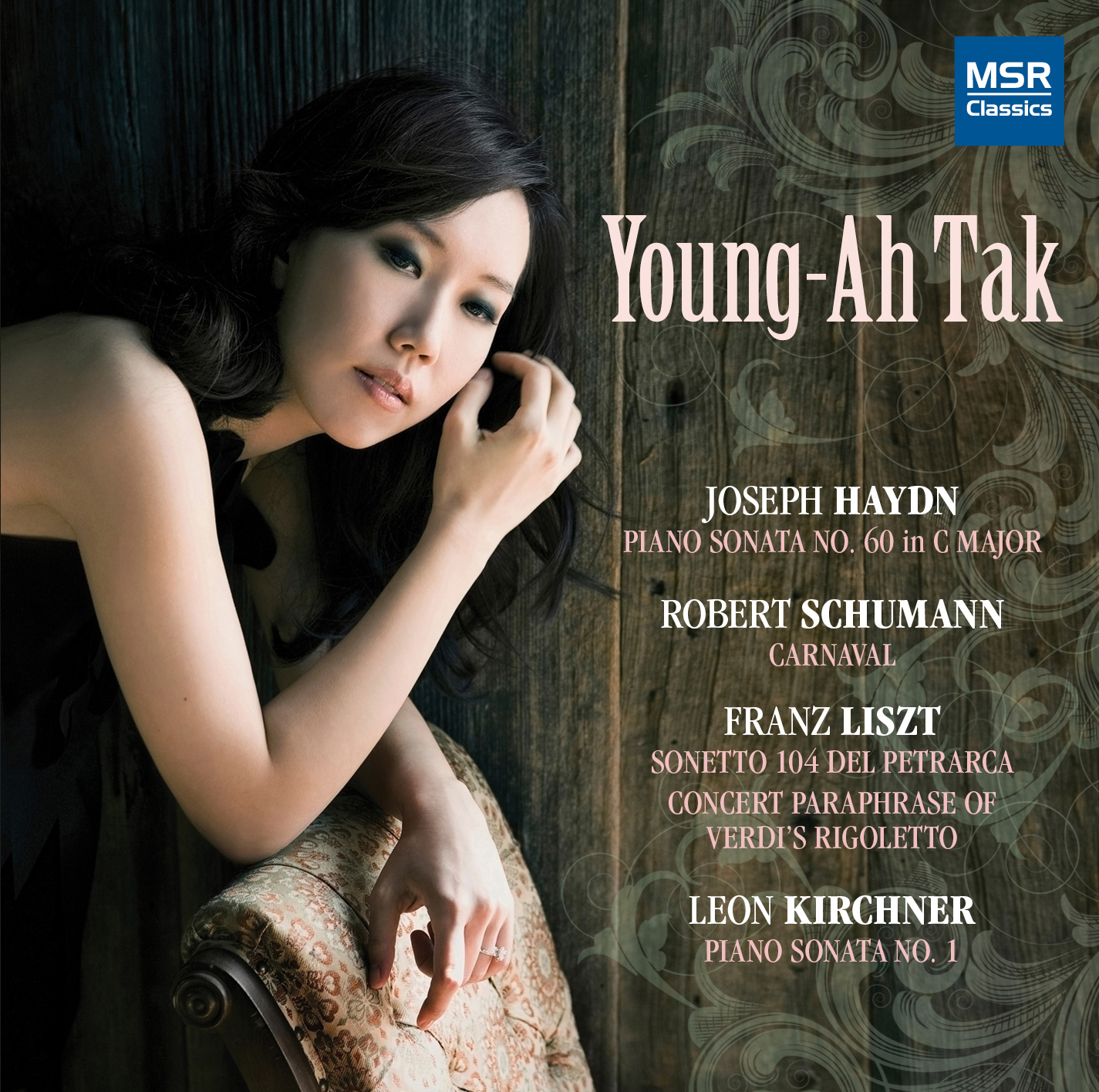

A lithe, quick, flexible touch on the keyboard, plus an unerring feeling for the rhythmic values inherent in the works she plays are combined in pianist Young-Ah Tak to make a technically challenging program seem deceptively easy. The Korea-born, U.S.-trained pianist essays an extremely varied program consisting of Haydn’s delightful Piano Sonata No. 60 in C major, Schumann’s wide-ranging and often deeply romantic Carnaval, Liszt’s superb paraphrase of themes from Verdi’s Rigoletto and the first really convincing account I have yet heard of his Sonetto 104 del Petrarca, plus a consummately fine performance of the sometimes disturbing Piano Sonata No. 1 by the late American composer Leon Kirchner (1919-2009).

The Haydn makes for a truly delicious curtain-raiser, what with its scintillatingly alert rhythms and smartly accomplished repeated notes in its opening movement and the nice sense of flow Ms. Tak imparts to the music. She brings off the lyricism of the Adagio with all the quasi-improvisatory spontaneity it deserves. And she keeps a steady feeling of irresistibly onward movement in the finale when encompassing three of the most egregious “wrong note” passages in the literature (deliberate examples of Haydn’s humor, we should add), the last of which gives the hilarious impression that the performer must be falling off the end of the bench!

Carnaval, perhaps Robert Schumann’s best loved major work as well as his most personal, provides Tak lots of opportunities for well-defined characterizations in its panoply of characters and situations inspired by personae from the commedia dell’arte and Schumann’s own life and loves. Perhaps the most telling of these “miniature scenes in quarter-notes” are “Chiarina,” Schumann’s portrait of his future bride Clara that captures her decided artistic temperament; “Chopin,” which pays its dedicatee the ultimate compliment of being cast in the style of a Nocturne; and “Aveu,” a deeply felt lover’s vow. Tak displays great flexibility in the way she adjusts to the changes in hand position, texture, rhythm, and color that occur continually throughout the 21 brief sections of this work.

Tak scores some of her best points in the Liszt part of the program, starting with the only satisfying account I have heard of Petrarch Sonnet 104, as she deftly follows the sense of a poem which describes all the deliciously unsettling sensations of being in love (“I fear, I hope and burn and freeze: / I fly above the sky and collapse to the earth.”) She sheds equal insight on the paraphrase of Verdi’s Rigoletto, which takes as its point of departure not the showy aria “La Donna è mobile,” but the vocal quartet “Bella fliglia dell’amore” which immediately follows it, cutting to the very heart of the opera.

The Kirchner sonata requires the utmost of the performer in its dissonances, driving rhythms, and a personal style of expression that recalls Bela Bartok to many observers, though Scriabin seems to me a likelier influence. Tak manages superbly the work’s brooding declamations and its passionate fast sections in which the composer seems to spray scattered notes at the listener like gun bursts. Though I admit I have yet to acquire a taste for Kirchner’s music, I feel that he could wish for no fairer or better balanced interpretation than Tak gives us here.