Reviews

FANFARE CD Review

Young-Ah Tak: Pursuing A Passion For Piano

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:2 of Fanfare Magazine.

By Jerry Dubins

November / December 2012

PDF Verson

PDF Verson

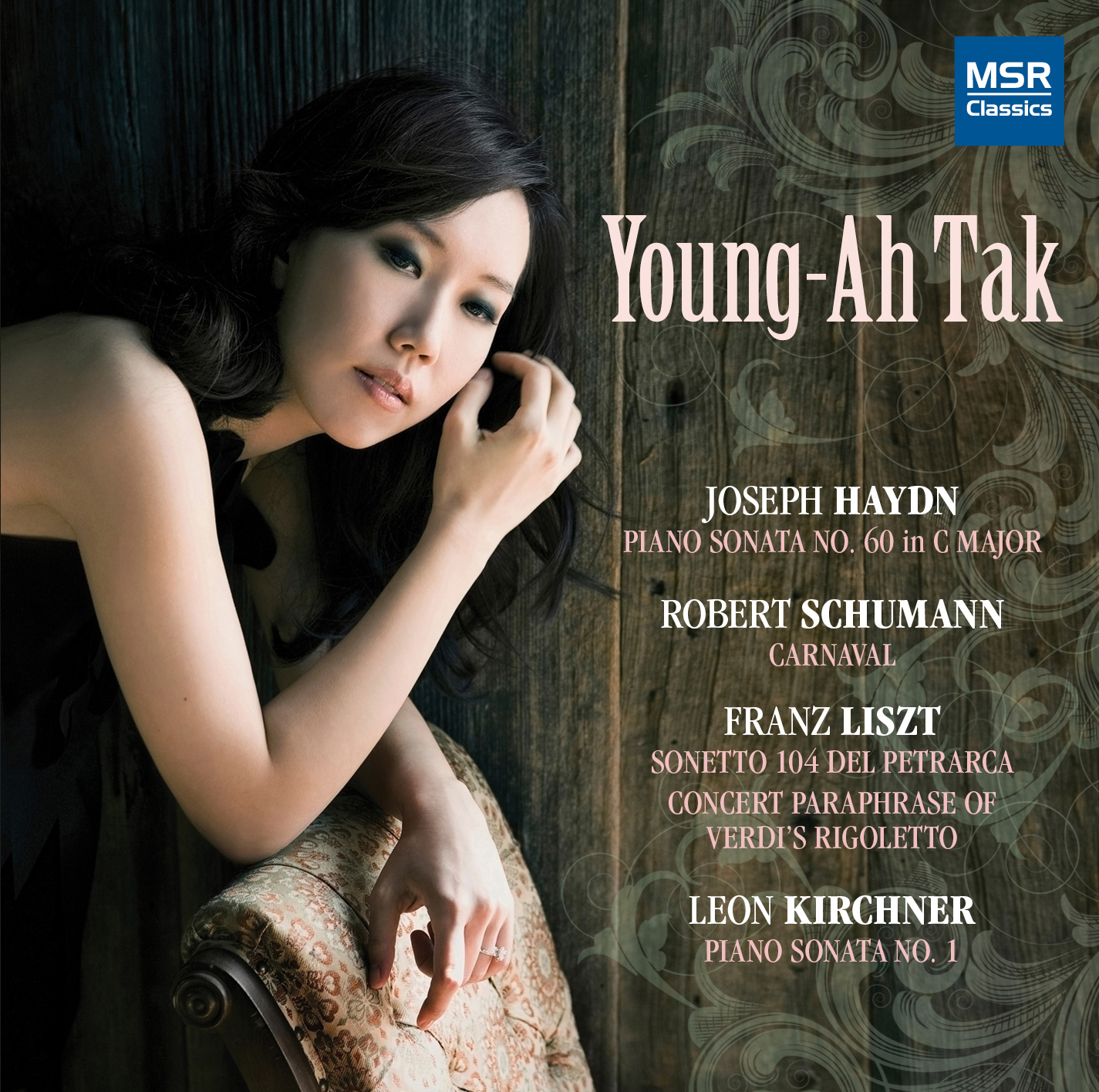

YOUNG-AH TAK • Young-Ah Tak (pn) • MSR 1375 (69:07)

YOUNG-AH TAK • Young-Ah Tak (pn) • MSR 1375 (69:07)

HAYDN Piano Sonata No. 60 in C.

SCHUMANN Carnaval.

LISZT Sonetto 104 del Petrarca. Concert Paraphrase on Verdi’s “Rigoletto.”

L. KIRCHNER Piano Sonata No. 1

Having trained at Juilliard, the New England Conservatory, and the Peabody Institute, and having studied with piano luminaries such as Leon Fleisher and Russell Sherman, Korean native Young-Ah Tak currently serves as an assistant professor of piano at Southeastern University in Florida. An avid advocate of contemporary music, Tak has performed at Sequenza 21 and at the Piano Century concert series in New York, and her debut recording of Judith Zaimont’s Wizards was released by Albany Records to great critical acclaim.

For her current CD, Tak sets herself a significant challenge, not just technically—each of these works represents its own technical challenges—but stylistically as well, with works that range from the Viennese Classical sensibilities of Haydn and the Romantic showpieces of Schumann and Liszt, to the distant shores of post-World War II American modernism in the sonata by Leon Kirchner.

If there’s a composer more joyful than Haydn, I don’t know who it is. His music is bursting at the seams with high spirits and hijinks meant to be laughed at out loud, and his C-Major Piano Sonata, Hob. XVI:60, is right at the top of the list for its quirking and quacking. Tak is so in tune with the music’s myriad jokes that her playing can only be described as mirthful. All the more reason then that I want to shake her by the shoulders for failing to observe the first movement’s exposition repeat. This is music you want to hear again, and it would only have added another two minutes to the performance.

In 1835, Schumann completed a 27-minute work he called Carnaval, subtitling it “Little Scenes on Four Notes.” Each of the work’s 21 miniatures is connected by a recurring motif and based on three or four notes in one of three permutations: (1) A, E♭, C, B; (2) A♭, C, B; and (3) E♭, C, B, A. This does not mean, however, that Carnaval is some sort of pre-Schoenbergian tone-row work or a precursor to the Minimalism of Terry Riley and Philip Glass. There are lots of other notes in these pieces, not just those that serve as a repeating code throughout the work. Tak takes no prisoners in this very difficult music. Her rhythmic incisiveness and technical fluency are marvels to behold, and her playing evinces both boldness and clarity of texturing I haven’t heard in this piece since Marc-André Hamelin’s stunning Schumann disc for Hyperion in 2006.

During his travels in Italy in the 1830s and 1840s, Liszt was inspired by his impressions of the land, its people, and its rich heritage of art and literature. Drawing upon the sonnets of the 14th-century Italian poet known as Petrarch, Liszt cast three of the poems—Nos. 47, 104, and 123—as songs for tenor and piano, simultaneously composing versions for piano alone. Several years later, he revised the three sonnets and incorporated them as the fourth, fifth, and sixth pieces in Book 2, Italy, of his Années de pèlerinage. Pianists often play one, two, or all three of them separate from their Années de pèlerinage setting and, based on numbers of recordings, the second of the group, No. 104, played here by Tak, seems to be the most popular.

A popular form of 19th-century musical entertainment was the dazzling virtuoso potpourri, medley, and paraphrase on popular, pre-existing works, usually operas. Liszt was no stranger to the medium, but he managed to elevate what were often little more than circus acts into a high art form. Verdi’s operas were a favorite though by no means exclusive target for Liszt’s treatment, and his Concert Paraphrase of Verdi’s “Rigoletto” stands out as a particularly fine example of the genre. Rather than work a number of the opera’s well-known arias into his piece, in the manner of a medley, Liszt focuses mainly on the act III quartet, Bella figlia dell’amore, making a brilliant, if fairly short, virtuosic showpiece of it. One wonders what Verdi might have thought of it. I can imagine some sharp-tongued barb from the Italian composer who once refunded the ticket price to an unhappy operagoer and advised him next time to stay at home.

This time I would have to compare Tak’s scintillating, glittering performance to that of Leslie Howard in his survey of Liszt’s complete oeuvre. Much as I admire Howard’s effort, I’d have to say that Tak is even more sparkling, assuredly a credit to her playing, but also to MSR’s bright, transparent recording.

What can I say about Leon Kirchner’s 1948 Piano Sonata No. 1? What can anyone say? Well, in a review of Tak’s live performance of the piece at a February 2012 recital, Richard Strom of the Herald Tribune wrote, “This sonata, with its avoidance of a recognizable tonal center and its use of repeated groups of dense and often dissonant clusters, is typical of its time. Occasional passages of melodic consonance were welcome, but it was difficult to determine where the piece was headed. Music of this kind often produces listener fatigue which diminishes its impact, even when played with the impressive skill heard on this occasion.”

I feel unqualified to judge Tak’s performance—or, for that matter, anyone’s performance—of this “atonal, sharply dissonant” piece. Tak’s recording of it, however, is far from its first. Leon Fleisher tackled it for Sony back in 1962, and there are versions of it by Robert Taub, Sara Laimon, and William Race, to name three others. For me, Kirchner’s sonata may get better with subsequent hearings, but it ain’t ever gonna get good.

An outstanding recital then by an exceptionally gifted pianist and accomplished artist, one that can be easily and enthusiastically recommended.

Jerry Dubins | This article originally appeared in Issue 36:2 (Nov/Dec 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.